When someone you love is struggling with substance use, the fear of an overdose is always there. It doesn’t matter if they’re using opioids, stimulants, or even prescription meds-overdoses don’t always come with warning signs you can see from across the room. But here’s the truth: overdose symptoms are often visible if you know what to look for. And if you learn them, you could save a life.

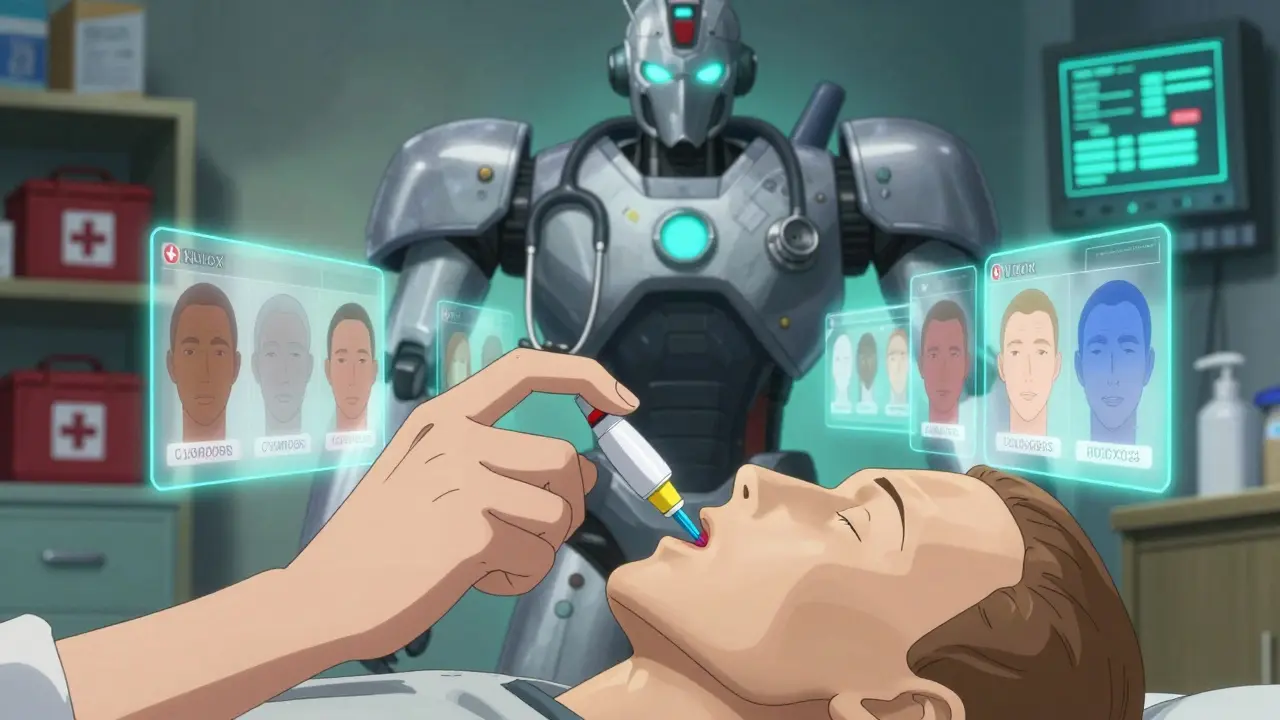

What an Overdose Actually Looks Like

Many people think an overdose means someone is passed out or shaking. That’s not always true. In fact, the most dangerous overdoses happen quietly. Someone might be breathing too slow, their skin turns gray or blue, and they don’t respond when you shake them or shout their name. That’s not just being high. That’s a medical emergency. For opioids like heroin, fentanyl, or prescription painkillers, there’s a clear pattern called the Opioid Triad:- Unresponsive - They won’t wake up, even if you rub their sternum (the center of their chest) firmly with your knuckles.

- Slow or stopped breathing - Fewer than one breath every five seconds, or no breathing at all.

- Cyanosis - Lips, fingernails, or skin turning blue or purple. On darker skin tones, this looks more like a grayish, ashen color.

- Limp body - Like a ragdoll, no muscle tone.

- Clammy or cold skin - Especially on the face.

- Gurgling or snoring sounds - Sometimes called a "death rattle" - this means their airway is blocked.

- High fever - Body temperature over 104°F (40°C).

- Seizures or tremors.

- Chest pain or racing heartbeat.

- Extreme confusion or paranoia.

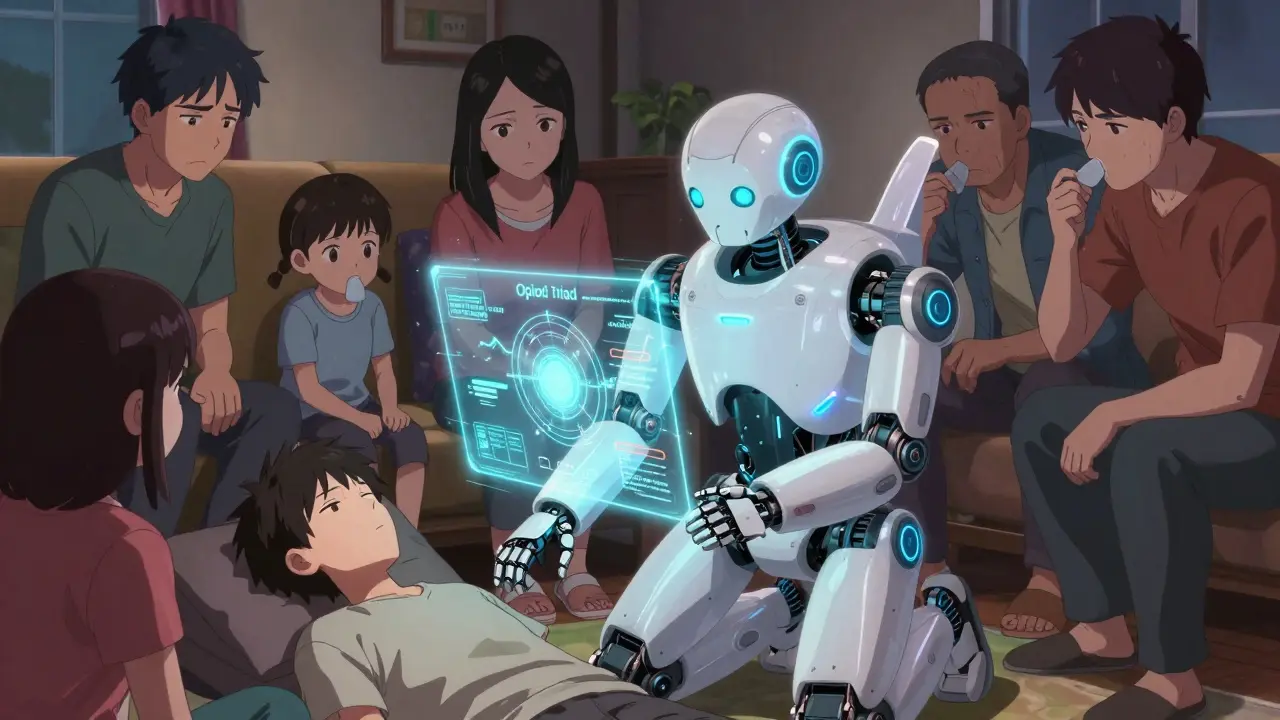

Why Family Members Are the First Responder

More than 78% of overdose deaths happen at home. That means the person who finds them first is usually a parent, sibling, partner, or child. Emergency services can take 10 minutes or more to arrive. In that time, brain damage starts after just 3-4 minutes without oxygen. Research from the Journal of Addiction Medicine shows that if a family member recognizes the signs and acts fast - especially by giving naloxone - the chance of survival goes up by 40%. In real cases, people have saved loved ones because they knew what to look for. One dad from Ohio told his story: "I’d watched the video twice. When my son stopped breathing, I didn’t hesitate. I gave the Narcan, cleared his airway, and started rescue breathing. EMS got there 12 minutes later. He woke up in the ambulance. That training saved him."How to Teach It - Without Scaring Everyone

Teaching family members doesn’t mean turning your living room into a medical class. It means practicing like you’re learning to use a fire extinguisher. Start with this simple framework: Recognize-Respond-Revive.- Recognize - Go through the signs together. Use photos or videos that show skin tone differences. Darker skin doesn’t turn blue - it turns gray. That’s critical.

- Respond - Practice yelling their name, shaking their shoulder, then doing a sternum rub. Show what unresponsiveness looks like. Use a mannequin or a pillow if you don’t have one.

- Revive - Get a training naloxone kit. They cost about $35 and come with no needles. Practice giving the spray in the nose. Do it three times. Make it normal.

Get the Tools You Need

You don’t need a medical degree. You need three things:- Training naloxone kits - These are fake. They look real, but they don’t contain medicine. Use them to practice. Order them from your local health department or harm reduction group.

- Skin tone guides - Many online resources show how cyanosis looks on different skin tones. Print one out and keep it with the kit.

- Scenario cards - Write down real-life situations: "Your daughter is slumped on the couch, doesn’t respond, and her lips are gray." Practice what you’d do.

What to Do If You Think Someone Is Overdosing

If you’re in a real situation, here’s exactly what to do:- Call 911 - Right away. Say: "I think someone is overdosing. They’re not waking up and not breathing."

- Give naloxone - Spray one dose into each nostril. No need to wait. Even if you’re not sure, give it. It won’t hurt someone who isn’t overdosing.

- Start rescue breathing - Tilt their head back, pinch the nose, give one breath every 5 seconds. Don’t stop until they breathe on their own or help arrives.

- Stay with them - Naloxone wears off in 30-90 minutes. The overdose can come back. Don’t leave them alone.

What About Fentanyl?

Fentanyl is the biggest threat now. It’s 50-100 times stronger than morphine. A tiny amount - smaller than a grain of salt - can kill. And it’s mixed into other drugs without the user knowing. That’s why fentanyl test strips are now part of training. They cost less than $1 each. You put a tiny bit of the drug in water, dip the strip, and wait 90 seconds. If it shows positive, don’t use it. If you’re already using, never use alone. Always have naloxone nearby.

Emotional Barriers - And How to Get Past Them

Many families avoid this training because they’re afraid. "What if I jinx it?" "What if I’m wrong?" "What if I have to watch them die?"" That fear is real. But the data doesn’t lie. People who train feel more confident. After training, 92% say they wish they’d done it sooner. One mom from Georgia said: "I thought I was being negative. Then my son overdosed. I used the training. He’s alive. I’d rather be wrong 100 times than be right once and lose him." Start small. Watch a 10-minute video together. Practice the sternum rub. Say the words out loud: "If they don’t wake up, we give Narcan."Where to Find Help

You don’t have to figure this out alone. These are free, trusted resources:- SAMHSA’s "Stop Overdose" curriculum - Used in every U.S. state. Downloadable videos and guides.

- Overdose Lifeline app - Has step-by-step videos, location finder for naloxone, and emergency checklists.

- Your local health department - Most offer free training sessions. Just call and ask.

- Harm reduction centers - They give out free naloxone and teach how to use it.

Final Thought: This Isn’t About Fear. It’s About Power.

You can’t control whether someone uses drugs. But you can control whether you know what to do when something goes wrong. This isn’t about judgment. It’s about survival. Teach your family. Practice together. Keep naloxone in the glovebox, the medicine cabinet, the purse. Make it normal. Because when seconds count, you won’t have time to Google it.What are the first signs of an opioid overdose?

The first signs are unresponsiveness (they don’t wake up when you shake them or rub their sternum), slow or stopped breathing (fewer than one breath every 5 seconds), and skin turning blue or gray - especially around the lips and fingernails. These are called the Opioid Triad. If you see two or more of these, act immediately.

Can naloxone harm someone who isn’t overdosing?

No. Naloxone only works if opioids are in the person’s system. If they’re not overdosing on opioids, giving naloxone won’t hurt them. It won’t cause a high or make them sick. It’s safe to use even if you’re unsure.

How do I recognize overdose symptoms on darker skin?

On darker skin, blue or purple lips and fingernails may not be visible. Instead, look for grayish, ashen, or pale skin - especially on the face, lips, or inside the mouth. The person will still be unresponsive and breathing very slowly or not at all. Skin tone guides are available for free from health departments to help with accurate recognition.

Is it safe to give naloxone more than once?

Yes. If the person doesn’t respond after 2-3 minutes, give a second dose. Fentanyl and other strong opioids can overwhelm one dose. Keep giving naloxone every 2-3 minutes until help arrives or they start breathing on their own.

Do I need training to get naloxone?

In 31 states, you can get naloxone at a pharmacy without a prescription or training. In 19 states, you need to complete a short training - often free and available online or at local clinics. Always check your state’s rules, but even if training isn’t required, it’s strongly recommended.

What if the person wakes up after naloxone?

Even if they wake up, they still need emergency medical care. Naloxone wears off in 30-90 minutes, and the overdose can return. Stay with them, keep them awake, and call 911. Don’t let them use drugs again - the risk of a second overdose is very high.

Can family members be legally protected if they give naloxone?

Yes. All 50 states and Washington D.C. have Good Samaritan laws that protect people who call 911 or give naloxone during an overdose. You can’t be arrested or sued for helping. These laws exist to encourage people to act without fear.

How often should we practice overdose response?

Practice every 3-6 months. Skills fade without repetition. Set a reminder to review the signs, check your naloxone’s expiration date, and do a quick drill. Even 10 minutes of practice every few months keeps everyone ready.

This is the kind of information every family needs. Not just for opioids, but for stimulants too. I used to think if someone was just sleeping it off, but now I know the difference. We keep naloxone in our kitchen drawer next to the coffee. It’s not morbid-it’s practical.

We did a drill last month. My brother pretended to pass out. We did the sternum rub, called 911, sprayed the naloxone. It felt weird at first. Now it feels like checking the smoke alarm.

If you’re scared to talk about this, you’re already losing time. Start small. Watch a video together. Say the words out loud. It saves lives.

I’m not a medic. I’m a mom. And I’m ready.

Look, I get that people want to save lives, but this whole ‘teach your family to be first responders’ thing is just another way to shift the burden of systemic failure onto grieving, untrained civilians. You’re telling people to become amateur paramedics while the healthcare system collapses and pharmacies charge $40 for a vial that should be free?

And don’t even get me started on the ‘fentanyl test strips’-like somehow a $1 strip is going to fix a drug supply poisoned by unregulated markets and corporate greed. It’s band-aids on a hemorrhage.

Yes, I know naloxone works. Yes, I know people die at home. But this isn’t empowerment-it’s resignation. We’re normalizing death because we won’t fix the root causes. You can’t CPR your way out of poverty, trauma, and pharmaceutical profiteering.

So sure, keep practicing. Keep spraying. But don’t pretend this is a solution. It’s just damage control for a society that refuses to heal.

I appreciate the practical advice. The opioid triad is clear. The skin tone note is critical-too many guides still only show pale skin.

One thing I’d add: don’t wait for all three signs. Two is enough. If someone’s unresponsive and their lips are gray, don’t wait for slow breathing to kick in. Act.

Also, the part about staying with them after naloxone? That’s the part people forget. I’ve seen it happen-someone wakes up, says ‘I’m fine,’ and walks away. Then they crash again. Naloxone isn’t a cure. It’s a pause button.

And yes, practice every few months. Muscle memory saves lives. Not knowledge. Memory.

It’s funny how we’ll teach people to use a fire extinguisher but act like talking about overdose response is taboo.

I used to think it was too dark. Too heavy. Then my cousin OD’d in the bathroom while we were watching TV. We didn’t know what to do. We panicked. He lived, but it took 14 minutes for EMS.

Now I have the training kit on my fridge. I showed my sister how to do the sternum rub. She laughed at first. Then she did it perfectly.

It’s not about fear. It’s about being prepared. Like locking your door. Like having a first aid kit.

And no, I don’t use emoticons. This isn’t a tweet. It’s survival.

Why are we even doing this? In Australia we just let people die if they’re dumb enough to do drugs. No one’s forcing them. Why waste resources training grandmas to spray noses? It’s like teaching people how to survive a plane crash because the airline won’t fix the engines.

And naloxone? It just encourages more use. People think they’re invincible now. ‘Oh, I’ve got Narcan.’ Great. Now you’re a junkie with a safety net.

Real solution? Stop funding rehab centers. Let the market decide. If you’re not willing to die for your habit, maybe you don’t deserve to live. Just sayin’.

They say you don’t know how much you love someone until you’re holding their limp body and screaming their name

And then you realize you’ve been waiting for this moment for years

And you don’t cry because you’ve already cried too much

You just spray

You just breathe

You just wait

And you pray

Not to God

To the clock

To the seconds

To the fact that you remembered

That you practiced

That you didn’t look away

That you didn’t wait for someone else to do it

Because you knew

You were the only one who could

And you were ready

I’ve seen this before. Someone posts a long, emotional guide about saving lives… then turns around and judges the person who overdosed. ‘They should’ve been stronger.’ ‘They should’ve listened.’

Look. I’m not here to coddle. But if you’re going to tell people how to save someone’s life, don’t then imply they deserved it. That’s not compassion. That’s hypocrisy.

And if you think this is just about ‘bad choices’-you’ve never held someone’s hand while they’re choking on their own breath.

It’s not about willpower. It’s about chemistry. And love. And knowing what to do when your heart breaks in real time.

Everyone’s talking about opioids but nobody’s talking about how stimulant overdoses are rising faster than ever. The fever, the seizures, the chest pain-those aren’t ‘just being high.’ That’s a heart attack waiting to happen.

And why is it that every guide shows a white person turning blue? I’ve seen Black and Brown people turn ashen, and no one mentions it. That’s dangerous.

Also-why is naloxone still not in every public bathroom? Why is it behind the counter like it’s contraband? We put defibrillators in gyms. Why not this?

It’s not about training people. It’s about making the tools accessible. And stopping the stigma that says ‘they brought this on themselves.’

That’s the real overdose.

I’m from India and we don’t talk about this here. People think if you use drugs you’re a criminal. No one teaches families. No one has naloxone. My cousin died last year. We didn’t know what was happening. We thought he was just drunk.

I cried for weeks. Then I found this post. I printed it. I showed my family. We practiced. We got the training kit from a clinic in Delhi.

It’s not about politics. It’s about love.

My sister asked me why we’re doing this. I said because if I don’t, no one will.

And now I’m not afraid anymore.

Just one thing-can someone translate this into Hindi? We need it.

Neurochemical cascade dynamics, when precipitated by exogenous opioid receptor agonism, induce respiratory depression via mu-opioid receptor-mediated inhibition of the pre-Bötzinger complex-this is the pathophysiological basis of the opioid triad. However, public health messaging often reduces this to heuristic heuristics, which, while pragmatically effective, risk epistemic oversimplification.

Furthermore, the proliferation of naloxone distribution initiatives, while statistically correlated with reduced mortality, introduces a potential behavioral disinhibition effect mediated by risk compensation theory-individuals may engage in higher-risk consumption paradigms under the perceived safety of pharmacological intervention.

That said, the empirical efficacy of family-based training protocols, particularly when coupled with multimodal sensory reinforcement (e.g., tactile sternum rub drills, visual cyanosis guides), demonstrates significant retention fidelity-89% per the cited meta-analysis. The cognitive load reduction achieved through procedural memory encoding is non-trivial.

Therefore, while structural interventions remain paramount, micro-interventions like these are necessary epiphenomena in the absence of macro-level policy reform. And yes-practice every 3-6 months. Because forgetting is not an option.