When your heart beats, it follows a precise electrical pattern. That pattern shows up on an ECG as waves - P, Q, R, S, T. The time between the start of the Q wave and the end of the T wave is called the QT interval. If this interval gets too long, it’s called QT prolongation. It doesn’t cause symptoms on its own. But it can trigger a deadly heart rhythm called torsades de pointes - a spinning, chaotic heartbeat that can turn into cardiac arrest. And it’s often caused by medications you might not think twice about.

What Actually Happens When QT Prolongs?

Your heart’s cells use tiny channels to let ions like potassium, sodium, and calcium flow in and out. One of those channels, called hERG, lets potassium leave the cell after each beat. That’s what resets the heart for the next cycle. When a drug blocks the hERG channel, potassium can’t leave fast enough. The cell stays electrically charged longer. That stretches out the QT interval on your ECG. The longer it stretches, the more likely your heart’s electrical system gets confused and starts firing erratically.Which Medications Are the Biggest Culprits?

Not all drugs that prolong QT are created equal. Some are high-risk, others low. The most dangerous ones are usually prescribed for heart problems - but even common meds can do it.- Class Ia and III antiarrhythmics: Quinidine, procainamide, sotalol, dofetilide. These are designed to fix arrhythmias, but they can cause them too. Sotalol raises QTc by 10-40 ms at higher doses. About 2-5% of patients on sotalol develop torsades.

- Antibiotics: Erythromycin and clarithromycin (macrolides) are big offenders, especially when taken with other drugs that slow their breakdown. Azithromycin is less risky but still flagged. Moxifloxacin (a fluoroquinolone) can add 6-10 ms to QTc.

- Antipsychotics: Haloperidol, ziprasidone, thioridazine. Ziprasidone has a black box warning from the FDA for sudden death risk. Even at normal doses, they can push QTc over 500 ms in vulnerable people.

- Antiemetics: Ondansetron (Zofran) is one of the most common triggers in emergency rooms. It’s used for nausea, but in older adults or those on other QT drugs, it can be dangerous.

- Antidepressants: Citalopram and escitalopram. The FDA capped citalopram at 40 mg daily (20 mg if you’re over 60) because of QT risk.

- Methadone: Used for pain and addiction, it’s a silent killer. Doses over 100 mg/day carry clear risk. Many patients on methadone maintenance have QTc over 470 ms - but with monitoring, serious events are rare.

- Newer cancer drugs: Vandetanib, nilotinib, sunitinib. These tyrosine kinase inhibitors are increasingly common and carry QT warnings. About 44% of the 27 approved agents in this class have QT prolongation listed as a side effect.

It’s not just the drug itself - it’s what else you’re taking. Combining two QT-prolonging meds multiplies the risk. A 2017 study found that haloperidol + ondansetron was far more dangerous than either drug alone. Even a common cold medicine like pseudoephedrine can add to the pile if you’re already on an antidepressant.

Who’s Most at Risk?

QT prolongation doesn’t hit everyone the same. Some people are walking time bombs without knowing it.- Women: About 70% of documented torsades cases happen in women. Postmenopausal and postpartum women are especially vulnerable. Their hearts repolarize slower naturally - so drugs push them over the edge faster.

- Older adults: Over 65. Kidneys and liver slow down. Drugs stick around longer. Electrolytes drop more easily.

- People with heart disease: Heart failure, prior heart attack, low ejection fraction - any structural damage makes the heart more sensitive to electrical chaos.

- Those with low potassium or magnesium: Diuretics, vomiting, diarrhea, eating disorders - all can drain these minerals. Low levels make QT prolongation worse.

- People with genetic risk: About 30% of drug-induced torsades happen in people with hidden genetic variants in the hERG channel. They might never have had a problem before - until a new medication flipped the switch.

When Should You Worry?

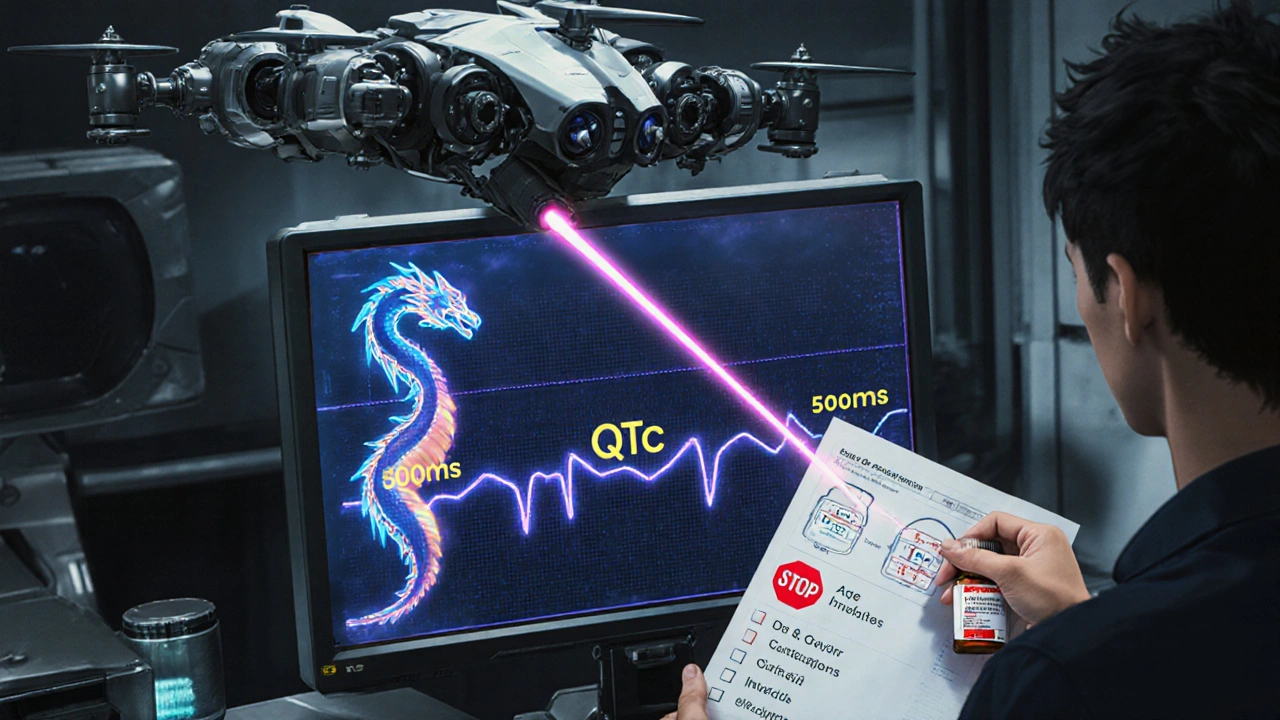

The numbers matter. Not all QT prolongation is dangerous.- QTc over 500 ms = high risk. Studies show torsades risk triples to quintuples at this point.

- An increase of more than 60 ms from your baseline = red flag. Even if your QTc is 480 ms, if it was 410 ms last month, that’s a problem.

- QTc between 450-499 ms = moderate risk. Watch for other factors: age, gender, drug combo, electrolytes.

Doctors use Bazett’s formula to correct QT for heart rate: QTc = QT / √RR. But it’s flawed. It overcorrects at slow heart rates and undercorrects at fast ones. Newer formulas like Fridericia’s are better, but most ECG machines still default to Bazett’s. That’s why interpreting ECGs requires experience.

What Should You Do?

If you’re prescribed a drug known to prolong QT, don’t panic - but don’t ignore it either.- Ask your doctor: "Is this drug on the crediblemeds.org list?" That site, updated quarterly, is the gold standard. It categorizes drugs as "Known Risk," "Possible Risk," or "Conditional Risk."

- Get a baseline ECG: Especially if you’re over 65, female, on multiple meds, or have heart disease. The European Society of Cardiology recommends this before starting high-risk drugs.

- Check electrolytes: Get a blood test for potassium and magnesium. Fix low levels before starting the drug.

- Review all your meds: Include OTCs, supplements, herbal products. Even St. John’s Wort can interfere with drug metabolism and raise QT risk.

- Monitor after starting: Get a repeat ECG within 3-7 days after starting or increasing the dose. That’s when levels peak.

- Know the warning signs: Dizziness, fainting, palpitations, sudden fatigue. If you feel any of these, get an ECG immediately.

Some hospitals now use electronic health record alerts that block dangerous combinations. One study showed this cut inappropriate prescribing by 58%. But not all systems have it. You may need to be your own advocate.

What About New Drugs?

The FDA and other agencies now use something called CiPA - Comprehensive in vitro Proarrhythmia Assay. It doesn’t just measure QT prolongation. It tests how drugs affect multiple ion channels and uses computer models to predict real-world arrhythmia risk. Since 2016, this has led to 22 drug failures in development. That’s good for safety - but bad for patients waiting for new treatments.Even newer drugs are being flagged. Retatrutide, a 2023 obesity drug, prolonged QTc by 8.2 ms in trials. It’s still on the market, but with monitoring requirements. AI tools are now being trained to spot subtle ECG patterns that predict torsades before QTc even crosses 500 ms. One 2024 study got 89% accuracy by analyzing waveform shape - not just the number.

Bottom Line

QT prolongation isn’t something you can feel. But it can kill you silently. Most cases are preventable. The key isn’t avoiding all risky drugs - it’s knowing when they’re dangerous for you. If you’re on any of the high-risk medications listed here, talk to your doctor. Ask for an ECG. Check your electrolytes. Review every pill in your bottle. Don’t assume your pharmacist or doctor caught every interaction. You’re the only one who knows your full history.The good news? Since systematic QT risk assessments became standard, drug-induced torsades has dropped by about 40% over the past decade. That’s because people started asking the right questions. You can be part of that change.

Can QT prolongation go away on its own?

Yes, in most cases. If the drug causing it is stopped and electrolytes are corrected, the QT interval usually returns to normal within days to weeks. But if the heart has already suffered damage from an arrhythmia, recovery may take longer - or require a pacemaker or ICD. Never stop a medication without medical supervision, even if you suspect QT prolongation.

Are natural supplements safe if they don’t list QT risk?

Not necessarily. Many herbal supplements aren’t tested for cardiac effects. Black cohosh, ephedra, and even high-dose green tea extract have been linked to QT prolongation in case reports. Just because it’s "natural" doesn’t mean it’s safe for your heart - especially if you’re on other meds.

Can exercise affect QT prolongation?

Exercise can temporarily shorten the QT interval - which is normal. But in people with drug-induced prolongation, intense physical activity can trigger arrhythmias. Avoid high-intensity workouts until your QTc is stable and your doctor says it’s safe. Light walking is usually fine.

Is QT prolongation the same as long QT syndrome?

No. Long QT syndrome is usually genetic and present from birth. QT prolongation from drugs is called "acquired" long QT syndrome. They look the same on an ECG, but the causes and treatments differ. Genetic forms require lifelong avoidance of certain triggers, while drug-induced cases often resolve when the medication is stopped.

How often should I get my QT interval checked if I’m on a high-risk drug?

For most people, a baseline ECG before starting the drug and a repeat one within 3-7 days is enough. If your QTc stays under 500 ms and you’re not on multiple risk drugs, monthly checks aren’t needed. But if you’re on methadone, sotalol, or multiple QT-prolonging agents, your doctor may recommend quarterly ECGs - especially if your dose changes or you develop new symptoms.

Can I still take ondansetron if I have a history of fainting?

Proceed with extreme caution. If you’ve fainted for no clear reason - especially during or after illness - you may have an underlying heart rhythm issue. Ondansetron can be dangerous in this group. Ask for an ECG before taking it. Alternatives like metoclopramide or dexamethasone may be safer, depending on your situation.

Do all ECG machines measure QTc accurately?

No. Many automated ECG readings are unreliable, especially if the heart rate is slow or the T wave is flat or biphasic. Manual measurement by a trained clinician is still the gold standard. Always ask if the QTc was measured by hand - not just read by the machine.

Man, I had no idea Zofran could do this. My grandma was on it after chemo and then passed out at the grocery store. They never checked her QT. Scary stuff.

THIS IS A BIG PHARMA COVER-UP. They know these drugs kill but keep selling them because they make billions. The FDA? Controlled. The ECG machines? Tampered with. They want you dependent. Watch your back.

Wait… so you’re saying a drug that fixes arrhythmia causes it? That’s like using fire to put out fire. Also, why do we even have hERG? Evolution messed up. And why is Bazett’s still used? Who approved this? Someone needs to explain this to me after I finish my chai.

Big thanks for breaking this down so clearly. I’m a med student and this is gold. Just had a patient on methadone + ondansetron - we checked her K+ and did an ECG right away. Saved her from a bad day. Knowledge is power, folks.

Excellent, thorough post. I’ve seen too many patients get flagged for QT prolongation after starting citalopram without baseline ECGs. The fact that 44% of new cancer drugs carry this warning is alarming - but not surprising. The key is proactive monitoring. Don’t wait for symptoms. Test early, test often. And yes, check St. John’s Wort - I’ve seen it mess with 5-HT2A and CYP3A4, which indirectly affects QT. Be vigilant.

Did you know the government is secretly replacing potassium in salt with something called ‘QT-activator’? They’re trying to make us all more vulnerable so they can sell more pacemakers. I saw a guy on YouTube with a chip in his neck that syncs with ECG machines. He said it’s from 2021. You think they’re watching us right now?

Wow. Just… wow. I’m on escitalopram. 10mg. Baseline QT was 420. Last week it was 475. I didn’t even know to check. I’m getting an ECG tomorrow. Thank you. Seriously. Thank you.

The clinical significance of acquired QT prolongation cannot be overstated. Prevention through baseline assessment and electrolyte optimization remains the cornerstone of risk mitigation. Institutional protocols must be standardized.

Bro… you’re telling me my Adderall + Zofran combo is risky? I thought I was just being productive. Also, why do all these drugs come from big pharma? Shouldn’t we be making our own meds in the garage? Like, I could probably make a safer one with CBD and turmeric. Just saying.

So… we’re living in a world where a pill for nausea can kill you? And the machine that reads your heart doesn’t even read it right? 🤦♂️ And we still trust doctors who rely on 1950s math? 😅 The system is a glitch. We’re all beta testers.

This is important information. Many do not know that electrolyte imbalance can amplify drug effects. Monitoring should be routine. Awareness saves lives.

From a cardiology perspective, the hERG blockade mechanism is textbook, but the real-world polypharmacy risk is where the rubber meets the road. When you stack a CYP3A4 inhibitor like clarithromycin with a QT-prolonging agent, you’re essentially creating a pharmacokinetic perfect storm. The FDA’s CiPA initiative is a step forward - it moves beyond QTc as a surrogate endpoint to functional proarrhythmic risk modeling. Still, we need better real-time ECG analytics. AI-driven T-wave morphology analysis? That’s the future.

Good stuff. If you’re on any of these meds, don’t freak out - but do talk to your doc. Ask for the ECG. Get your K+ checked. It’s not that hard. You’ve got this.

Wow. So we’re all just… walking time bombs? And the only thing keeping us alive is a doctor who remembers to check a number that a machine gets wrong half the time? 🤷♂️ I’m just here for the memes and the existential dread.