When you're running a clinical trial, not every side effect is a red flag. But how do you know which ones actually need to be reported right away? The difference between a serious adverse event and a non-serious one isn’t about how bad the patient feels-it’s about what actually happened to them. Confusing intensity with outcome is the most common mistake in safety reporting, and it’s costing time, money, and attention away from real risks.

What Makes an Adverse Event "Serious"?

An adverse event (AE) is any unwanted medical occurrence during a clinical trial, whether or not it’s linked to the drug or device being tested. But only some of these count as serious. The definition isn’t subjective-it’s written in law. According to the FDA and ICH E2A guidelines, an event is serious if it meets any one of these six criteria:

- It caused death

- It was life-threatening (meaning the patient was at immediate risk of dying)

- It required hospitalization or extended an existing hospital stay

- It caused permanent disability or significant incapacity

- It led to a congenital anomaly or birth defect

- It required medical or surgical intervention to prevent one of the above outcomes

That’s it. No more, no less. A migraine that knocks someone out of work for a day? Not serious. A broken rib from a fall? Not serious-unless the fall was caused by dizziness from the drug and the patient ended up in the ER with internal bleeding. Then it is.

Many people mix up "severe" with "serious." A severe headache is intense. A serious headache is one that leads to a stroke. One describes how bad it feels. The other describes what it did to the person’s life.

When Do You Have to Report a Serious Event?

Timing matters. If an investigator learns about a serious adverse event, they must report it to the sponsor immediately-within 24 hours. That’s not a suggestion. It’s a legal requirement under 21 CFR 312.32. The clock starts ticking the moment the person responsible for patient care knows about it, even if they’re not sure whether the drug caused it.

Once the sponsor gets the report, they have deadlines too. For a serious event that isn’t life-threatening, they must file with the FDA within 15 calendar days. If it’s life-threatening, that window shrinks to 7 days. And if it’s unexpected-meaning it wasn’t listed in the study’s safety profile-the timeline doesn’t change, but the urgency does. These reports go straight to the FDA’s MedWatch system, where safety teams scan for patterns.

For Institutional Review Boards (IRBs), the rule is usually 7 days for serious events. Non-serious events? They often don’t get reported to the IRB at all-unless the study protocol says otherwise. Most sites only include them in monthly or quarterly summaries.

What About Non-Serious Events?

Non-serious adverse events are everything else. They’re still important. They’re tracked. They’re documented in Case Report Forms (CRFs). But they don’t trigger emergency alerts. These are the headaches, nausea, rashes, or fatigue that patients experience but don’t need hospitalization, don’t cause lasting harm, and don’t threaten life.

The FDA and NIH classify these by intensity, not outcome:

- Mild: Noticeable, but doesn’t interfere with daily life. No treatment needed.

- Moderate: Disrupts normal activity. May require over-the-counter meds or a doctor’s visit.

- Severe: Intense symptoms. May need prescription treatment, but still doesn’t meet the six serious criteria.

Here’s the catch: a severe rash that itches like crazy but doesn’t cause infection or scarring? Non-serious. A mild fever that lasts three days but leads to hospitalization for dehydration? That’s serious.

Why Do People Get This Wrong?

Because it’s easy to confuse. A clinical research coordinator sees a patient with "severe anxiety" and thinks, "That’s serious." But unless that anxiety led to a suicide attempt, self-harm, or hospitalization, it’s not serious under the rules. The same goes for "severe pain"-if it’s managed with oral meds and the patient goes home, it’s not reportable as a serious event.

Studies show this isn’t just a few mistakes. In 2019, nearly 37% of reports sent to IRBs as "serious" didn’t actually meet the criteria. In 2020, almost 29% of expedited safety reports submitted to the EMA were incorrectly classified. At UCSF, over 40% of AE reports in 2022 needed clarification because the initial classification was wrong.

Why does this happen? Lack of training. Overworked staff. Pressure to report "everything just in case." But when you flood the system with noise, you bury the signal. Dr. Janet Woodcock of the FDA said it plainly: "The current system is overwhelmed by non-serious events reported as serious, diluting attention from truly critical safety signals."

How to Get It Right Every Time

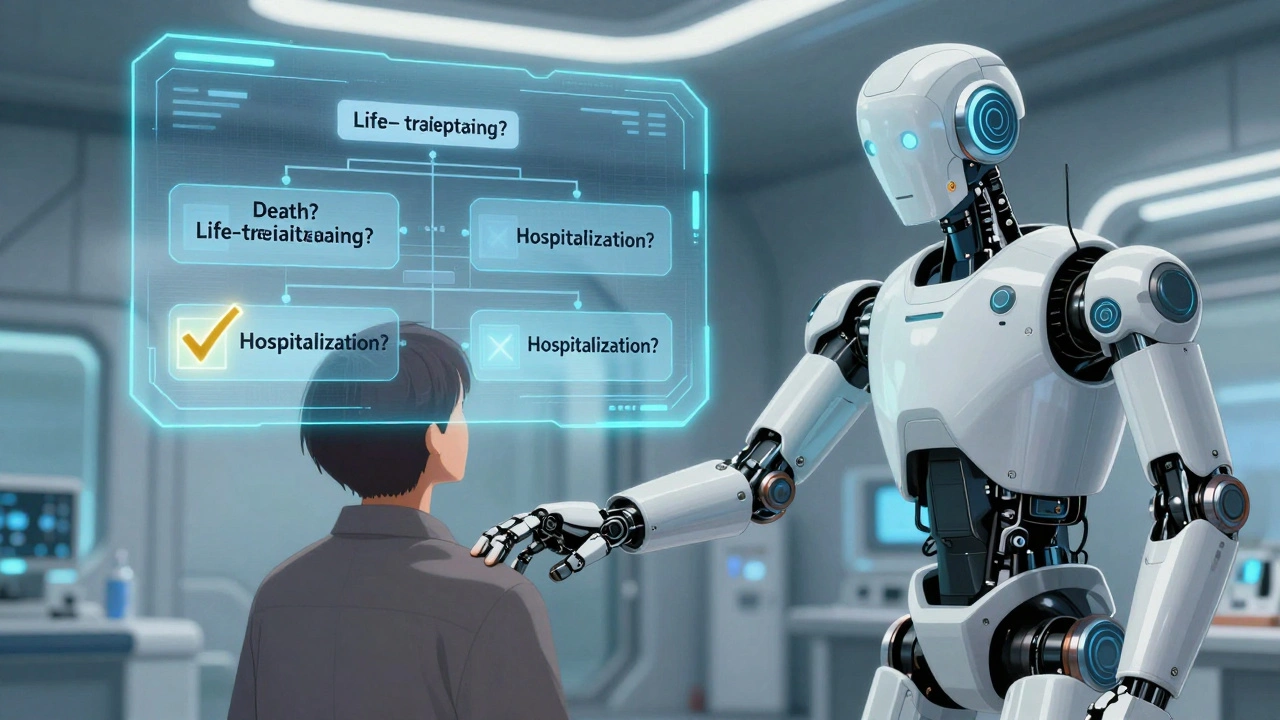

There’s a simple decision tree you can use. Ask these four questions:

- Did the event cause death?

- Was it life-threatening?

- Did it require hospitalization or extend a hospital stay?

- Did it cause permanent disability or significant incapacity?

If the answer is "yes" to any one of these, it’s serious. Report it immediately. If the answer is "no" to all, it’s non-serious. Document it, track it, include it in your monthly summary-but don’t hit the emergency button.

Use tools. The Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 5.0 is the standard for grading severity. But seriousness? That’s a separate checklist. Most sponsors now use both side by side. AI tools are getting better-89.7% accuracy in classifying seriousness as of 2023-but they still need human review. Never fully automate the final call.

Training is non-negotiable. ICH E6(R2) requires all staff to be trained on seriousness criteria before starting a trial. Top institutions require annual refreshers. If your site doesn’t do this, you’re not compliant.

The Cost of Getting It Wrong

This isn’t just about rules. It’s about resources. In 2022, the pharmaceutical industry spent $1.89 billion on adverse event reporting. Over 60% of that went to processing events that didn’t need to be reported as serious. That’s millions of dollars spent on paperwork that doesn’t improve safety.

At SWOG Cancer Research Network, 32% of SAE reports had to be corrected after submission. That’s 18.5 full-time hours every week just fixing mistakes. At one major hospital, a single misclassified report delayed an IRB review by nearly 10 days. That’s weeks lost on trial timelines.

And then there’s the risk: if you under-report serious events, you miss signals that could save lives. If you over-report, you desensitize reviewers. Both are dangerous.

What’s Changing?

The system is evolving. The EU’s Clinical Trials Regulation, fully in force since 2022, standardized seriousness definitions across all 27 member states. That cut cross-border reporting errors by over a third.

The FDA’s 2023 draft guidance proposes tiered reporting: even within serious events, the timeline might vary based on severity. A life-threatening event gets priority. A serious event that caused hospitalization but no organ damage? Still serious, but maybe not 7-day urgency.

And AI is stepping in. Natural language processing tools are being tested to auto-sort reports. MIT’s 2023 pilot showed a 47% reduction in processing time. But here’s the truth: machines can flag, but humans must decide. The final call always rests with a trained reviewer who understands context.

For example: a patient with cancer gets a fever after treatment. Is it an infection? Is it tumor-related? Is it serious? Only someone who knows the patient’s history, their baseline, and the trial’s inclusion criteria can answer that. Algorithms can’t replace clinical judgment.

Final Takeaway

Reporting adverse events isn’t about being cautious. It’s about being precise. You don’t report every side effect. You report every outcome that changes a person’s life. Death. Disability. Hospitalization. Life threat. That’s it.

Train your team. Use the decision tree. Double-check before you hit submit. And remember: a severe symptom is not a serious event. A serious event is one that changes the course of a life. Get that right, and you’re not just following rules-you’re protecting people.

man i used to think 'severe' meant 'serious' too... until my buddy got hospitalized from a 'mild' fever that turned into sepsis. guess what? the drug wasn't even the cause. but if we hadn't reported it? who knows. point is, it's not about how much it hurts, it's about what it does. 🤯

I can't believe people still confuse this... Seriously? A headache? Really? If your patient has a headache and you report it as serious, you're not being cautious-you're being negligent. The FDA doesn't need your emotional interpretations, they need facts. And if you can't tell the difference, maybe you shouldn't be near a clinical trial. 🙄

they're just using this to cover their own incompetence. if you report everything, no one notices the real stuff. they want you to be a robot. but the real danger? they're hiding the bad drugs by drowning them in noise. #BigPharma

the ctcae v5.0 grading and seriousness criteria are two entirely different axes. severity is intensity, seriousness is outcome. most sites mix them because training is rushed. i've seen coordinators flag a grade 3 nausea as serious because it's 'severe'. it's not. it's just bad. the difference matters because it changes the regulatory burden and patient safety focus

i'm just saying... if a patient gets a rash and it itches like hell, that's not serious. but if they scratch it open and get an infection? now you've got a problem. it's not the rash. it's the cascade. always think downstream. 🙏

this is why we need better training. not more rules. just better teaching. i watched a new coordinator cry because she thought a 2-day fever was serious. she wasn't lazy. she was just never shown how to think about it.

yo. i used to be the guy who reported every sneeze. then i saw a real SAE get buried under 400 false positives. now i use the four-question filter like a bible. if it doesn't hit one of those? it's not serious. period. stop being a spreadsheet jockey. be a clinician.

in india we used to report everything because we were scared of audits. now we use the decision tree. big difference. less paperwork. more focus on real issues. also... no emojis here 😅

you think this is bad? wait till you work in a developing country where they don't even have proper EDC systems. people report 'serious' because they don't know what else to do. training isn't a luxury. it's survival

i've seen this play out in three different countries. the pattern is always the same: overworked staff, vague protocols, no time for training. the solution isn't more tech. it's more empathy. someone needs to sit with the coordinator and walk them through one real case. not a slide deck. a story.

the 60% waste metric is misleading. it doesn't account for the downstream cost of under-reporting. a single missed signal in oncology can lead to hundreds of preventable deaths. the system is inefficient, yes-but the cost of error is existential. we're not talking about paperwork. we're talking about mortality.

Per ICH E6(R2) Section 4.17, all personnel involved in the conduct of clinical trials shall receive adequate training regarding the identification and reporting of adverse events, with specific emphasis on the distinction between severity and seriousness. Non-compliance constitutes a significant deviation from GCP and may result in regulatory action.

usa is the only country that still uses this outdated system. europe standardized it in 2022. why are we still wasting time on this? we got ai that can read brainwaves but we can't fix a reporting form? this is why we're falling behind. #america

i remember a case where a patient had a mild cough. no hospitalization. no breathing issues. just a cough. but it was the first sign of pulmonary fibrosis from the drug. turned out to be life-threatening in 3 weeks. we caught it because we didn't ignore the 'non-serious' one. sometimes the quiet ones are the loudest.

why even bother? they'll just bury it anyway. report it or don't. doesn't matter. they're not looking for safety. they're looking for liability. 😒