Key Takeaways

- Angioedema can be triggered by the same inflammatory pathways that cause sinusitis.

- Both histamine‑mediated and bradykinin‑mediated forms of angioedema have links to upper‑airway infections.

- Identifying the overlap helps avoid misdiagnosis and speeds up proper treatment.

- Lab tests for C4 and C1‑INH levels, plus a CT scan of the sinuses, are essential for a full work‑up.

- Targeted therapy-antihistamines, corticosteroids, C1‑INH concentrate or bradykinin antagonists-combined with sinus‑specific care often resolves both problems.

What Is Angioedema?

When you see sudden swelling of the lips, face, tongue or airway, you are looking at Angioedema is a rapid, deep‑layer swelling of the skin and mucous membranes caused by fluid leakage from blood vessels. The swelling can be painful, sometimes life‑threatening if the airway narrows. Angioedema falls into two major pathways: histamine‑driven (often allergic) and bradykinin‑driven (often genetic or drug‑induced).

What Is Sinusitis?

Sinusitis is inflammation of the paranasal sinuses that leads to mucus buildup, congestion, facial pain and sometimes fever. It can be acute (lasting up to four weeks) or chronic (persisting longer than 12 weeks). Viral infections kick‑off most cases, but bacterial superinfection, allergies and structural issues such as nasal polyps can keep the sinuses inflamed.

Why The Two Can Appear Together

Both conditions share a common denominator: an overactive inflammatory response in the upper airway. Here’s how the biology overlaps:

- Mast cells are immune cells that release histamine and other mediators when they encounter an allergen or irritant. In sinusitis, mast cell activation fuels nasal swelling; the same mediators can travel to deeper facial tissues and trigger angioedema.

- Histamine is a vasoactive amine that increases blood‑vessel permeability, causing the characteristic swelling of allergic angioedema. Histamine spikes are common during viral or allergic sinus infections.

- When the bradykinin pathway dominates, Bradykinin is a peptide that widens blood vessels and makes them leaky, leading to deep‑tissue swelling in hereditary or ACE‑inhibitor‑induced angioedema. Upper‑airway infections raise bradykinin levels indirectly by activating the kallikrein‑kinin system.

- C1 esterase inhibitor (C1‑INH) is a protein that regulates the complement and kallikrein‑kinin cascades; deficiency or dysfunction lets bradykinin run unchecked. Many patients with hereditary angioedema report recurrent sinus infections, likely because the same dysregulated cascade fuels sinus mucosal edema.

- ACE inhibitors are blood‑pressure medications that block the breakdown of bradykinin, increasing the risk of drug‑induced angioedema. ACE‑inhibitor users often present with sinus congestion before the swelling spreads to the lips or throat.

In short, whether the trigger is an allergen, a virus, a medication, or a genetic deficiency, the same leaky‑vessel mechanisms can manifest as both sinusitis and angioedema.

Spotting the Overlap in Patients

Clinicians can look for a few red flags that point to a combined picture:

- Recurrent facial swelling that coincides with sinus infection episodes.

- Unexplained angioedema in a patient on an ACE inhibitor.

- Family history of hereditary angioedema plus chronic sinus complaints.

- Persistent nasal blockage despite standard antihistamine or steroid therapy.

- Elevated serum C4 levels (low C4 suggests a bradykinin‑mediated process).

Diagnostic Pathway

Getting the diagnosis right means addressing both sides of the coin. Follow these steps:

- Clinical interview: Document timing, triggers, medication list, family history, and any previous episodes of swelling.

- Physical exam: Look for swelling of the lips, tongue, or periorbital areas; check for sinus tenderness, nasal polyps, or post‑nasal drip.

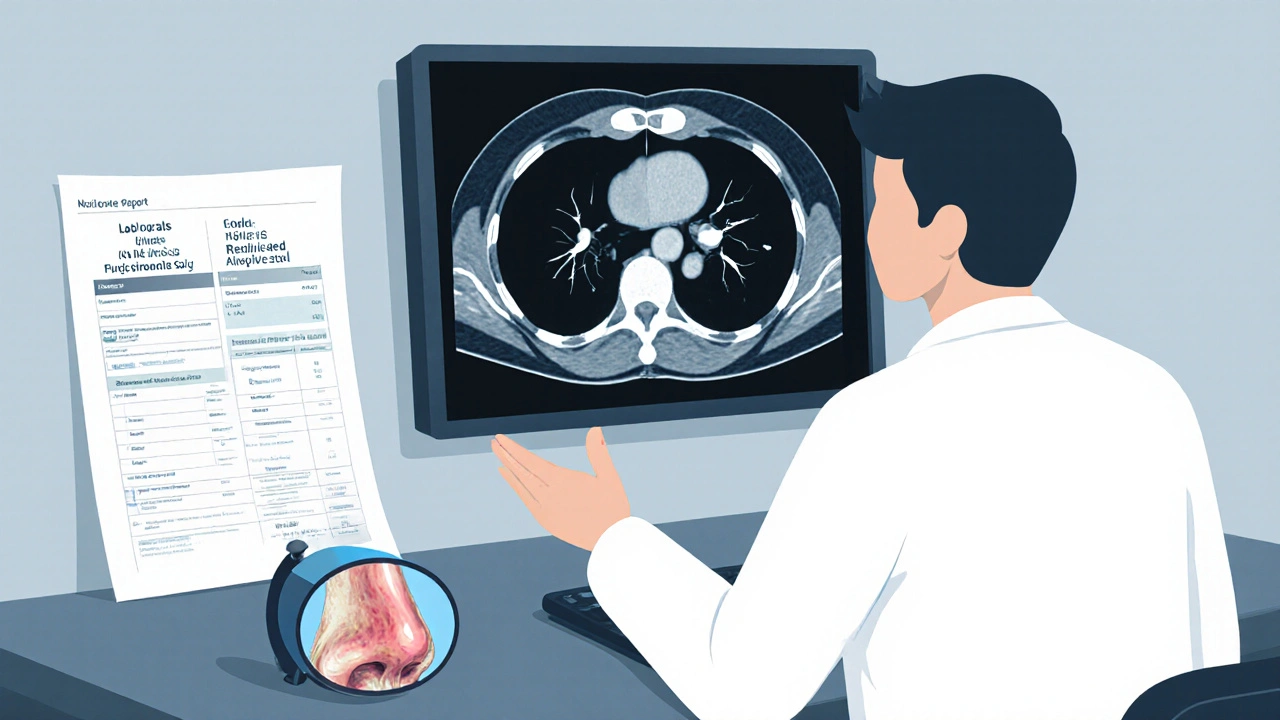

- Imaging: A non‑contrast CT scan is the gold standard for visualising sinus opacification, bony anatomy and any obstructive lesions. It also helps rule out deeper infections that could exacerbate angioedema.

- Laboratory work‑up:

- C4 complement level - low in hereditary or acquired bradykinin‑mediated angioedema.

- C1‑INH functional assay - confirms deficiency.

- Allergy testing - pinpoints histamine‑driven triggers.

- Endoscopic evaluation: Nasal endoscopy can reveal polyps or mucosal edema that may be contributing to both conditions.

| Angioedema Type | Key Mediator | Typical Sinus Connection | Management Overlap |

|---|---|---|---|

| Histamine‑mediated | Histamine | Allergic rhinitis often precedes sinus infection; antihistamines help both. | Antihistamines, intranasal steroids. |

| Bradykinin‑mediated (hereditary) | Bradykinin | Chronic mucosal edema creates a breeding ground for bacterial sinusitis. | C1‑INH concentrate, icatibant, sinus irrigation. |

| ACE‑inhibitor‑induced | Bradykinin | Drug‑related nasal congestion often mimics sinusitis. | Stop ACE inhibitor, give bradykinin antagonist, treat sinus infection if present. |

Management Strategies

Effective treatment tackles both the swelling and the sinus inflammation.

Acute Angioedema Relief

- Histamine‑driven episodes: oral antihistamines (cetirizine, loratadine) and short‑course corticosteroids.

- Bradykinin‑driven episodes: C1‑INH concentrate (Berinert, Cinryze) or a bradykinin‑B2 receptor antagonist (icatibant).

- Airway monitoring: always have epinephrine auto‑injectors on hand for severe cases.

Chronic Sinus Care

- Saline nasal irrigation twice daily to clear mucus and reduce mucosal edema.

- Intranasal corticosteroid spray (fluticasone) to suppress inflammation.

- For refractory cases, functional endoscopic sinus surgery (FESS) removes obstructive tissue and improves drainage.

- Address underlying allergies with immunotherapy when indicated.

Co‑ordinated Approach

When a patient shows both conditions, a combined plan works best:

- Stabilise any life‑threatening swelling first.

- Start sinus‑specific therapy (irrigation, steroids) within 24‑48hours to cut inflammation.

- If hereditary angioedema is confirmed, enrol the patient in a prophylactic C1‑INH program.

- Review medications-switch ACE inhibitors to ARBs if blood‑pressure control is needed.

- Schedule follow‑up ENT and immunology appointments to monitor progress.

Checklist for Clinicians

- Ask about recent sinus infections when a patient presents with facial swelling.

- Check medication list for ACE inhibitors or neprilysin inhibitors.

- Order C4 and C1‑INH levels if angioedema is recurrent or unexplained.

- Obtain a sinus CT if swelling persists beyond 48hours or if symptoms suggest obstruction.

- Begin antihistamines or corticosteroids promptly; add bradykinin‑targeted therapy if labs point to that pathway.

- Educate patients on early warning signs of airway compromise.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can sinusitis cause angioedema on its own?

Sinusitis itself doesn’t directly trigger the deep‑tissue swelling known as angioedema, but the inflammatory mediators released during a sinus infection-especially histamine and bradykinin-can spill over and provoke swelling in nearby facial tissues.

What tests confirm hereditary angioedema in a patient with chronic sinusitis?

Measure serum C4 (usually low) and perform a functional C1‑INH assay. Genetic testing for SERPING1 mutations can provide definitive confirmation.

Should I stop my ACE inhibitor if I develop sinus congestion?

If the congestion is accompanied by any facial swelling, it’s wise to switch to an ARB (angiotensin‑II receptor blocker) under doctor supervision, as ACE inhibitors raise bradykinin levels and can trigger angioedema.

Are there lifestyle changes that help both conditions?

Yes. Staying well‑hydrated, using saline nasal sprays, avoiding known allergens, and quitting smoking reduce mucosal inflammation and lower the risk of both sinusitis flare‑ups and angioedema episodes.

When is emergency care required?

If swelling involves the tongue, lips, or throat and begins to affect breathing or speech, call emergency services immediately. This is true regardless of the underlying cause.

Really appreciate the way this piece ties together the histamine and bradykinin pathways. It makes it easier for clinicians to see why a patient might swing between allergic and hereditary angioedema. The checklist at the end is a solid practical tool. I also like the reminder to double‑check ACE‑inhibitor use before assuming it’s just a sinus thing. Thanks for a clear rundown.

Nice breakdown of the overlap between sinus inflammation and facial swelling it helps keep the two from being treated in isolation.

Ths article really shed light on how bradykinin can creep into sinus mucosa and cause that stubborn swelling we see in many patients. I think many docs miss that link until it becomes a real emergency. Good reminder to order C4 and C1‑INH when the usual antihistamines dont work. Also, reminding folks to stop ACE inhibitors early can save a lot of trouble.

From a pathophysiological perspective, the confluence of the kallikrein‑kinin cascade and the classical histaminergic axis represents a quintessential example of immunological cross‑talk that underpins both sinonasal disease and angioedema. In the acute phase, mast cell degranulation liberates histamine, prostaglandins, and leukotrienes, which amplify vascular permeability not only in the nasal mucosa but also in adjacent periorbital and labial dermis. Concomitantly, activation of factor XII initiates the intrinsic coagulation pathway, culminating in generation of bradykinin via plasma kallikrein, a potent vasoactive peptide that preferentially targets the deeper submucosal chambers. The synergistic effect of these mediators explains why patients with viral or allergic sinusitis can precipitously develop marked facial swelling, particularly when C1‑INH regulatory mechanisms are compromised. Genetic mutations in SERPING1 resulting in quantitative or functional C1‑INH deficiency exacerbate this scenario by allowing unbridled kallikrein activity, thereby creating a feedback loop of bradykinin overproduction. Clinically, this manifests as recurrent angioedema episodes that are temporally linked to sinus infection flares, a pattern that may be overlooked without vigilant longitudinal assessment. Diagnostic work‑up should therefore incorporate complement profiling-specifically C4 levels and functional C1‑INH assays-alongside high‑resolution sinus CT imaging to delineate mucosal edema, ostiomeatal obstruction, and possible polyposis. Therapeutically, a dual‑pronged approach is warranted: short‑acting antihistamines and corticosteroids to blunt the histaminergic surge, combined with targeted bradykinin antagonism (e.g., icatibant) or C1‑INH concentrate replacement in bradykinin‑dominant phenotypes. In chronic management, prophylactic subcutaneous C1‑INH or lanadelumab can reduce attack frequency, while endoscopic sinus surgery addresses anatomic contributors to persistent inflammation. Moreover, medication reconciliation to eliminate ACE‑inhibitors or neprilysin inhibitors is a non‑negotiable step, given their propensity to elevate bradykinin levels. Finally, patient education regarding early signs of airway compromise, adherence to nasal saline irrigation, and avoidance of known allergens constitutes the cornerstone of preventing future episodes. In sum, recognizing the intertwined nature of these pathways empowers clinicians to deliver comprehensive, evidence‑based care that mitigates both sinusitis and angioedema morbidity.

While the clinical recommendations are exhaustive, I must note that the sheer volume of suggested interventions may overwhelm a primary‑care setting. One might consider a tiered algorithm: first address airway safety, then select anti‑histamine or bradykinin‑targeted therapy based on lab results, and finally refer for ENT evaluation. The prose, though formal, borders on the pedantic, which could alienate practitioners seeking concise guidance.

In the grand tapestry of human suffering, the convergence of sinusitis and angioedema is a reminder that our bodies are but vessels of chaos, yearning for order. Yet, the article paradoxically offers a roadmap, suggesting that through measured intervention we may impose structure upon this disorder. It is both a cautionary tale and a beacon of hope, illustrating the delicate balance between biochemical destiny and therapeutic will.

Great info.

Whoa, this reads like a medical thriller! The drama of swelling, the suspense of a blocked airway… I can barely keep my eyes open reading all those labs and scans. Someone get this guy a microphone, because the drama queen in the room is definitely the bradykinin cascade.

Super helpful rundown 🙌 Especially the tip about swapping ACE inhibitors – saved me a trip to the ER last winter. Also, the emoji reminder to hydrate 🧊💧 is a nice touch.

People don’t realize that big pharma pushes ACE inhibitors to keep us dependent while hiding the bradykinin side effects. If you’re not careful, they’ll have you choking on your own meds. Stay vigilant and question your prescriptions.

This article is a mess of jargon and half‑baked advice. The author seems to think sprinkling buzzwords substitutes for real clinical insight. It’s an insult to readers who actually need clear guidance.

Thanks for laying out a step‑by‑step plan that balances both specialties. I’ve seen patients who bounced between ENT and immunology without a cohesive strategy; this checklist could bridge that gap. Remember to involve patients in shared decision‑making, especially when discussing prophylactic C1‑INH versus surgical options.