Breastfeeding Medication Safety Checker

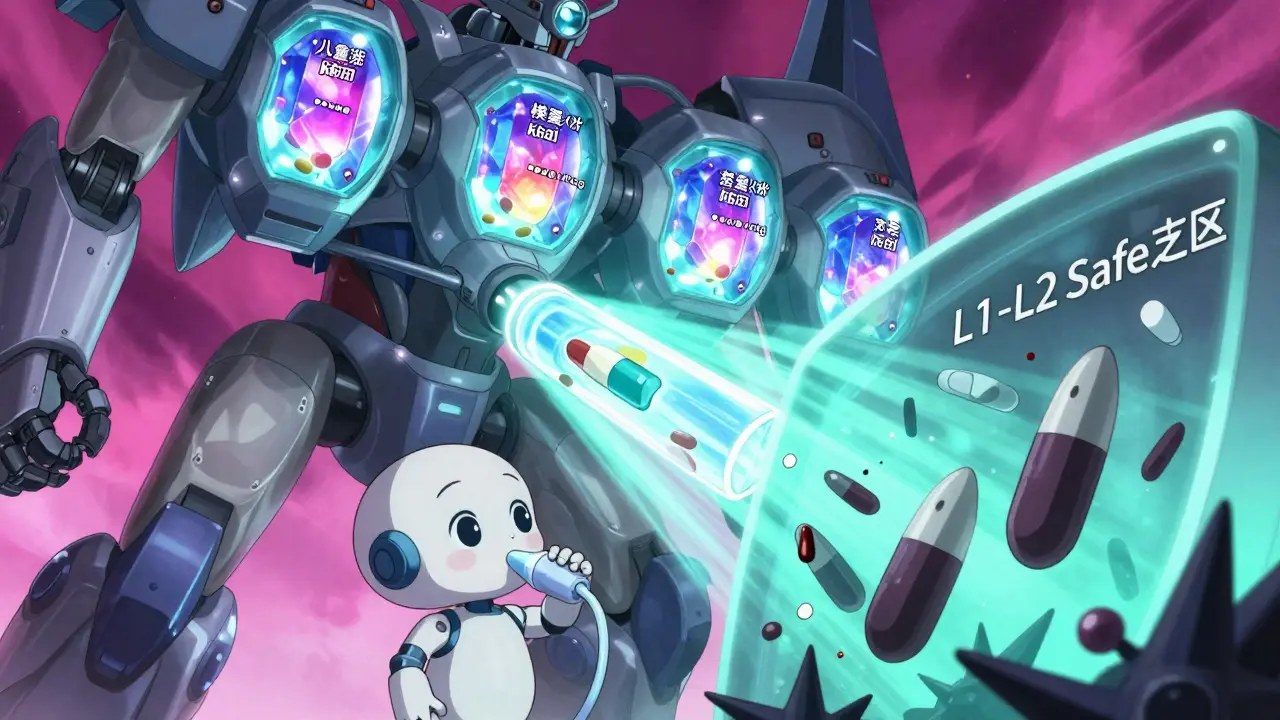

This tool checks medications against Hale's breastfeeding safety classification system (L1-L5). Enter a medication name below to see its classification and key safety information.

Medication Classification

Safest

No known adverse effects in breastfed infants. Safe to use while breastfeeding.

Drug Transfer

Minimal (< 1% of maternal dose)

Baby Risk

Very low

Key Information

Common uses: This medication is commonly used for...

Recommended timing: Take after breastfeeding to minimize infant exposure.

Monitoring needed: Usually none, but check for any unusual symptoms in your baby.

When a mother takes a medication while breastfeeding, it doesn’t just stay in her body. It can end up in her breast milk-and then in her baby. This isn’t something to panic about, but it’s also not something to ignore. Around 56% of breastfeeding mothers take at least one medication, from pain relievers to antidepressants. Yet, fewer than 2% of babies show any real side effects from it. The truth is, most medications are safe. The real challenge? Knowing which ones are safe, and how to use them wisely.

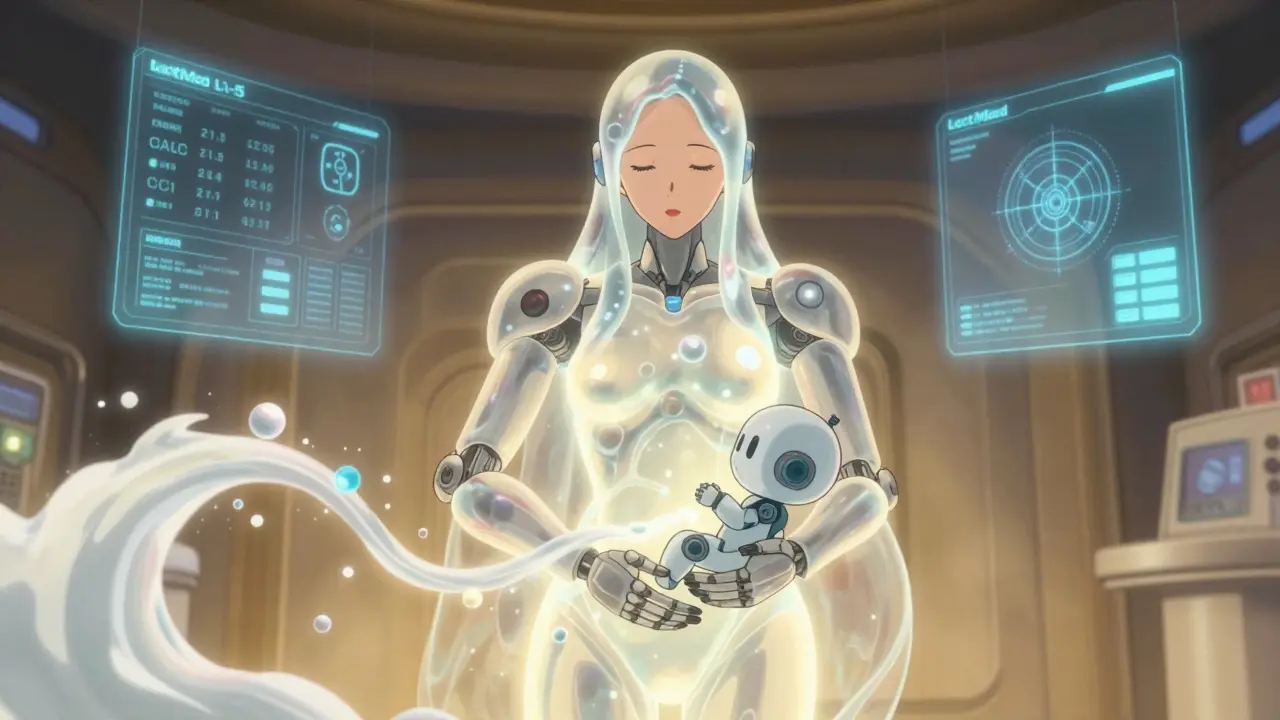

How Medications Get Into Breast Milk

Medications don’t magically appear in breast milk. They move from the mother’s bloodstream into the milk through a process called passive diffusion. Think of it like a sponge soaking up water: the drug molecules follow concentration gradients, moving from areas of higher concentration (mom’s blood) to lower concentration (milk). But not all drugs do this the same way. Four key factors decide how much of a drug ends up in milk:- Molecular weight: Drugs under 200 daltons slip through easily. Larger molecules, like heparin or insulin, barely make it.

- Lipid solubility: Fats love fat. Drugs that dissolve well in lipids (like antidepressants or benzodiazepines) cross into milk more readily.

- Protein binding: If a drug is tightly bound to proteins in the blood (over 90%), it can’t float freely into milk. Warfarin and most NSAIDs are examples.

- Half-life: The longer a drug stays in the body, the more it can build up in milk. A drug with a 24-hour half-life is riskier than one cleared in 4 hours.

There’s also something called ion trapping. Breast milk is slightly more acidic than blood (pH 7.2 vs. 7.4). Weakly basic drugs-like lithium, amphetamines, or certain antihistamines-get pulled into milk and can concentrate there at ratios as high as 10:1. That doesn’t mean they’re dangerous, but it does mean you need to be extra careful with them.

Right after birth, the gaps between milk-producing cells are wider. That means drugs can get into colostrum more easily. But here’s the twist: colostrum volume is tiny-only 30 to 60 milliliters a day. So even if the concentration is high, the total amount the baby gets is still very small. By day 5, milk production ramps up, but the cell gaps tighten. The system balances out.

The LactMed Database and Hale’s Classification System

Not all resources are created equal. Two tools stand out: LactMed and Dr. Thomas Hale’s classification system. LactMed, run by the U.S. National Library of Medicine, is the most comprehensive database out there. It covers over 4,000 drugs, with detailed data on 3,500 of them. It’s free, updated regularly, and used by over 1.2 million people every year. It gives you numbers: how much drug shows up in milk, how much the baby absorbs, potential side effects. But it’s technical. If you’re not a pharmacist, it can feel overwhelming. Enter Hale’s L1-L5 system. It’s simpler. It turns complex data into clear categories:- L1: Safest. No known adverse effects. Examples: acetaminophen, ibuprofen, penicillin.

- L2: Probably safe. Limited data, but no reported harm. Examples: sertraline, fluoxetine, ciprofloxacin.

- L3: Moderately safe. Potential risk. Use if benefit outweighs risk. Examples: lithium, certain SSRIs, diazepam.

- L4: Possibly hazardous. Evidence of risk. Only use if no alternatives. Examples: cyclosporine, amiodarone.

- L5: Contraindicated. Proven risk. Avoid completely. Examples: radioactive iodine, chemotherapy drugs like methotrexate.

While LactMed gives you the raw data, Hale’s system gives you the decision. Clinicians use both: LactMed to dig deep, Hale to make quick calls.

Common Medications and Their Real-World Risk

Most mothers need pain relief, antibiotics, or mental health support. Here’s what’s actually safe:- Analgesics: Acetaminophen and ibuprofen are L1. They’re in breast milk at less than 1% of the maternal dose. No known harm. Avoid aspirin in high doses-it can cause Reye’s syndrome in infants.

- Antibiotics: Penicillins, cephalosporins, and macrolides like azithromycin are L1. Even metronidazole, once feared, is now considered safe at standard doses. The baby might get a bit of loose stool, but that’s not dangerous.

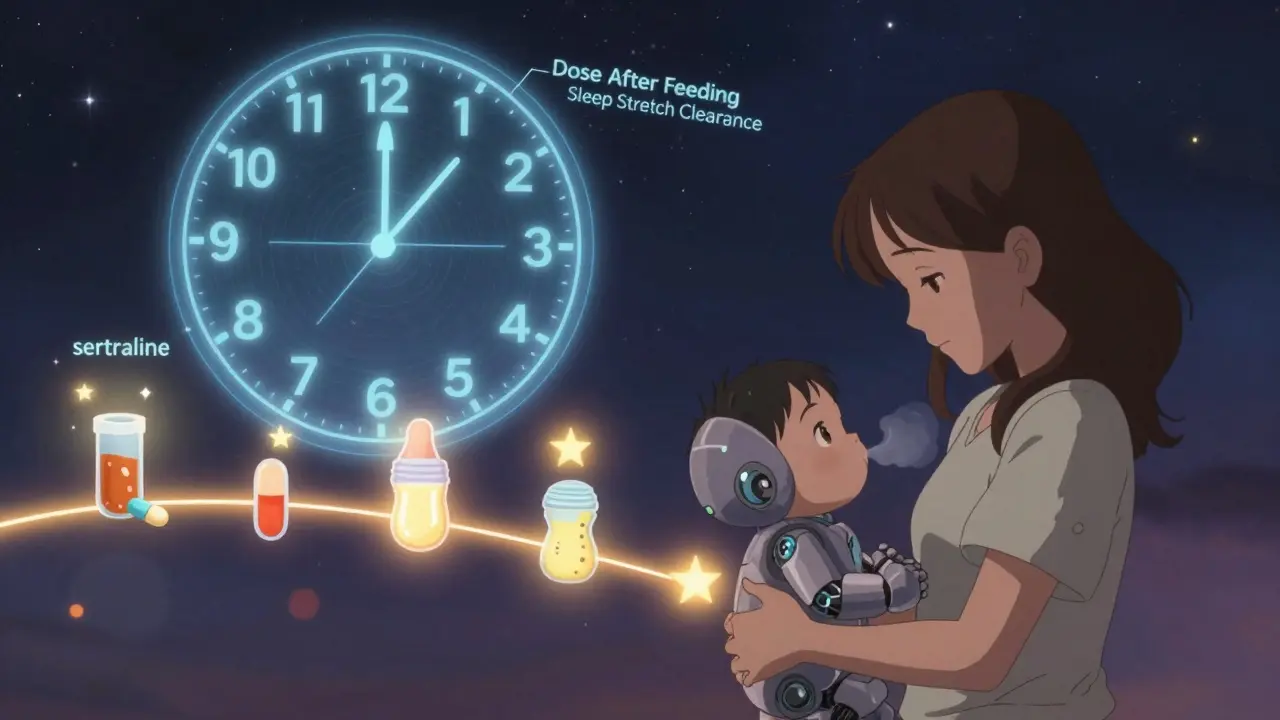

- Psychotropics: Sertraline (Zoloft) is the gold standard for breastfeeding mothers with depression. It’s L2. Fluoxetine (Prozac) is also L2, but it sticks around longer, so it’s less ideal. Benzodiazepines like lorazepam (Ativan) are L3-use short-term and avoid bedtime dosing.

- Thyroid meds: Levothyroxine is L1. It’s not absorbed well by babies, so even if it’s in milk, it doesn’t affect them.

- Birth control: Progestin-only pills (mini-pill) are safe. Estrogen-containing pills can reduce milk supply-avoid them in the first 6 weeks.

On the other hand, avoid these unless absolutely necessary:

- Lithium: L3. Can cause toxicity in babies-requires close monitoring.

- Chemo drugs: L5. All of them. Stop breastfeeding during treatment.

- Radioactive iodine: L5. Used for thyroid cancer. Must stop breastfeeding for weeks.

- Heroin, cocaine, meth: L5. Not just dangerous for the baby-illegal and life-threatening.

When and How to Take Medications

Timing matters more than you think. If you take a single daily dose, take it right after breastfeeding. That way, your blood levels are highest right after the feed-and lowest when the baby next eats. For drugs with a short half-life, like ibuprofen (2-4 hours), this cuts infant exposure by up to 80%. For multiple daily doses, take the pill right before the baby’s longest sleep stretch-usually after the nighttime feeding. That gives your body time to clear the drug before the next feeding. Topical medications? Usually safe. Creams, patches, sprays. Unless you’re applying them directly to the nipple. Then wash thoroughly before feeding. Even then, the amount absorbed by the baby is tiny.What to Watch for in Your Baby

Most babies show no signs. But if you’re concerned, look for:- Unusual sleepiness or fussiness

- Poor feeding or weight gain

- Diarrhea or vomiting

- Rash or unusual crying

If you notice any of these, don’t stop breastfeeding. Call your doctor. Most of the time, it’s not the medication. But if it is, switching to a safer alternative is almost always possible.

Studies show that 78% of lactation consultants see at least one mother per month who was wrongly told to stop breastfeeding because of a medication. That’s a huge gap in knowledge. You don’t have to be a doctor to know this: fewer than 1% of medications require you to stop breastfeeding.

What’s New and What’s Coming

The science is moving fast. The LactMed database now includes 350 herbal products and 200 supplements-because moms are using them, and we need data. Apps like LactMed On-the-Go make it easier than ever to check a drug while you’re in the pharmacy or at the pediatrician’s office. The InfantRisk Center’s MilkLab study has measured actual drug levels in breast milk from over 1,250 mothers. That’s real-world data, not theory. And the FDA is now pushing drug companies to include breastfeeding women in clinical trials. That means in five years, we’ll have better data on newer drugs like biologics and targeted cancer therapies. By 2030, personalized lactation pharmacology might be standard. Imagine a simple blood test that tells you how fast you metabolize a drug-and how much will end up in your milk. That’s not sci-fi. It’s already being tested.Final Takeaway: You Don’t Have to Choose

You don’t have to choose between being a healthy mom and being a breastfeeding mom. You can be both. Most medications are safe. The key is not fear-it’s information. Use LactMed. Ask your doctor about Hale’s categories. Time your doses. Watch your baby. And if someone tells you to stop breastfeeding because of a pill-ask them for the evidence. Chances are, they’re wrong.Breastfeeding is powerful. Medications are tools. Used wisely, they don’t break the bond-they protect it.

So let me get this straight-some lady’s taking ibuprofen and now the baby’s gonna turn into a chemically enhanced zombie? LOL. I’ve seen moms panic over a single Advil like it’s heroin. Meanwhile, my kid drank breast milk while I was on antibiotics, Adderall, and whiskey. He’s now a 6’2” college freshman who doesn’t cry when he stubs his toe. Chill the hell out.

While the article presents a generally accurate overview, it fails to account for inter-individual pharmacokinetic variability in lactating women, particularly with respect to CYP450 enzyme polymorphisms and breast milk pH fluctuations. For instance, the assumption that sertraline is universally L2 overlooks case reports of infant sedation in mothers with reduced CYP2D6 activity. Furthermore, the omission of maternal body mass index as a covariate in drug distribution modeling represents a significant methodological gap in clinical translation.

Can we just talk about how wild it is that we’ve turned motherhood into a 24/7 biohazard assessment? 😭

You’re not just a mom anymore-you’re a walking pharmacology lab with a nursing pillow. I mean, I get it, science is cool, but at what point do we stop treating breastfeeding like a nuclear reactor and start treating it like… love?

My kid’s been on breast milk since day one while I took Zoloft, Tylenol, and one too many margaritas. He’s 8 now. Reads Shakespeare. Doesn’t have a single chemical trace of me in his soul. Just vibes. And maybe a little anxiety. But hey, that’s just inherited.

Interesting breakdown. I’ve been on levothyroxine since postpartum and never thought about how little gets into milk. My pediatrician just said ‘keep going’ and never explained why. This makes me feel way less guilty about taking it. Also, the timing tip about dosing after feeding? Game changer. I’ve been taking mine at breakfast and wondering why my baby’s so fussy after the 2am feed.

Oh wow. So we’re supposed to be grateful that Big Pharma hasn’t outright murdered our babies yet? 🙃

Let’s be real-this whole ‘L1-L5’ system is just a marketing pamphlet disguised as science. Who even decided these categories? Some guy in a lab coat with a PowerPoint and zero kids? I’ve seen moms get kicked out of support groups for taking ‘L3’ meds. Meanwhile, the same doctors who say ‘avoid lithium’ are prescribing Xanax for anxiety like it’s candy.

And don’t even get me started on ‘Herbal Products’ in LactMed. So chamomile tea is now a ‘drug’? My grandma brewed it in a sock and called it ‘calm.’

Stop scaring moms. Just give us the truth: most pills are fine. The real danger is the fear.

So if I take a pill after nursing, does that mean my milk turns into a time capsule? 🤔

Also, I just took a nap and woke up with a 2-hour-old baby who’s now crying like I’m the villain in a Netflix drama. Is it the Zoloft? The lack of sleep? The fact that I accidentally used my ex’s shampoo? 😭

Anyway, LactMed is my new BFF. Even if I don’t understand half the words.

There’s a quiet revolution happening here. We used to treat breastfeeding like a religious vow-pure, sacred, untouchable. Now we’re treating it like a biological system with variables. That’s progress.

The real win isn’t the LactMed database or Hale’s categories-it’s that mothers are finally being treated like rational agents instead of vessels. We’re not just feeding babies. We’re managing our own health, too. And that’s not weakness. It’s wisdom.

Also, if someone tells you to stop breastfeeding because of a pill, ask them if they’ve ever taken one themselves. If they haven’t, their opinion is just noise.

…I didn’t know about ion trapping… and I didn’t realize colostrum volume was so small… I’ve been so worried about every single thing I’ve taken… I think I’ve been overthinking it… maybe I should check LactMed… but I’m scared I’ll find something bad… and then I’ll feel worse…

Did you know the FDA has been pressured by pharmaceutical lobbyists to downplay drug risks in breastfeeding? They don’t want you to know that most studies are funded by the companies that make the drugs. And LactMed? It’s run by the NIH-but who funds the NIH? Big Pharma. The ‘safe’ drugs? They’re only safe if you ignore the 10-year follow-up studies that got buried. And why is lithium L3? Because the baby’s thyroid gets damaged… but no one talks about how the mother’s mental health is being sacrificed to keep the milk flowing. The system is rigged. You’re being manipulated into compliance. Wake up.

Thank you for this comprehensive overview. I particularly appreciate the distinction between pharmacokinetic principles and clinical decision-making frameworks. As a nurse practitioner specializing in maternal-child health, I have consistently recommended LactMed to patients, though many find Hale’s system more accessible. I would only add that maternal adherence to dosing schedules significantly impacts infant exposure, and that non-pharmacological interventions-such as cognitive behavioral therapy for depression-should be prioritized where feasible, even if medication remains necessary. The goal is not merely safety, but optimal maternal-infant bonding, which is compromised by undue anxiety. This post helps reduce that burden.